Trump’s Watergate?

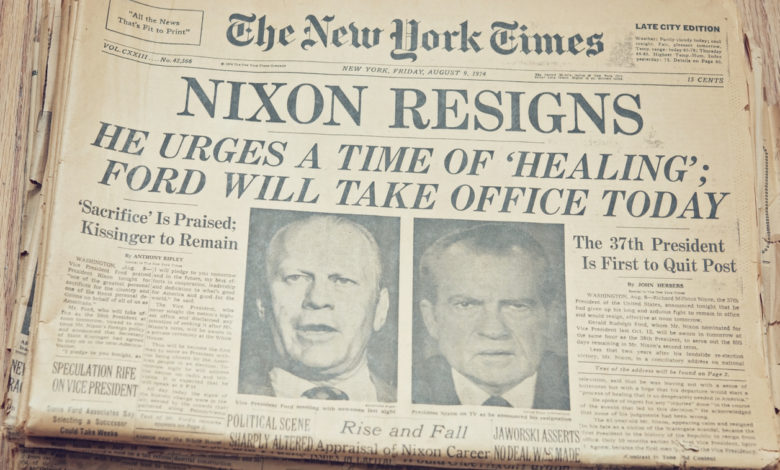

Shortly after midnight on June 17, 1972, an alert security guard at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. noticed something amiss. Someone had placed tape over the locks on doors leading from the complex’s underground garage to the office building. The guard thought little of it, so he removed the tape and went about his business. When he returned a short time later, however, he discovered that someone had re-taped the locks. This time he called the police. Three plainclothes officers working the overnight “bum squad” responded and promptly arrested five hapless burglars whose bumbling lookout man had been distracted watching The Attack of the Puppet People on the television in his hotel room across the street.

Over the next two years, the investigation of this mundane burglary—and relentless press coverage—led to the convictions of not only the burglars but of a total of 48 people, many of them top officials in the Nixon administration, not to mention the resignation of the president of the United States.

To paraphrase an old English proverb, mighty consequences from small offenses sometimes grow.

Now, an offense committed by relatively unknown people acting at the state level could grow into “Trump’s Watergate.” Of course Trump, unlike Nixon, is already out of office, but he has other worries—like protecting his fortune, keeping the door open to run again in 2024, and staying out of jail.

If state and federal law enforcement authorities convene grand juries to investigate the low-level GOP officials who signed and submitted phony electoral certificates in the 2020 election, the entire conspiracy to overturn the 2020 election could unravel.

So far, there has been no visible indication that Attorney General Merrick Garland has any appetite to launch a sweeping investigation into Team Trump’s conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Garland has said nothing about it. His silence could just be prudential—it can be unwise for a prosecutor to alert prematurely the subjects of investigations. Or he may be reluctant to pursue such a case at all, perhaps due to some combination of his cautious nature, fear that it might be perceived as partisan political retribution, the difficulty of drawing clear lines between protected speech and conspiracy, and the difficulty of proving criminal intent in the mind of a cult figure whose bizarre mental state is unfathomable.

But none of those inhibitions should apply to a routine investigation into the mundane crimes implicated by the creation, execution and submission to the government of phony electoral documents. Quite the opposite: The failure to investigate that kind of obvious election fraud would smack of political calculation.

Law enforcement officials investigating the phony documents, as distinguished from a broader conspiracy, would not have to search for a crime—they already have the smoking guns, documents that are fraudulent on their face. Nor would they need to search for the culprits. The fraudsters signed their names to the phony documents, many of them proudly recording the act on video.

This open-and-shut election fraud is a gift to Garland and his federal prosecutors. Without having to expend any political capital by opening a sweeping investigation targeting Donald Trump or those around him, prosecutors could chip away at the broader conspiracy.

The targets of the investigation would be the people who signed and transmitted the phony elector certificates, not Donald Trump.

A total of 59 individuals from five states signed the documents. We know virtually nothing about them. They are not national figures, and largely are not public figures, except perhaps in state and local circles. They seem to be a fairly representative sample of Americans with quotidian jobs, nice families, and cute pets—not hardened denizens of the criminal underworld.

Can you imagine what would happen if 59 otherwise respectable burghers were hauled before a grand jury, facing a very real prospect of going to jail? How long do you think it would take for some or all of them to seek plea deals that would keep them out of prison? How quickly will they line up to identify those who told them to do it?

In very short order, investigators would have a mountain of testimony identifying every single person who induced or aided and abetted the pseudo-electors in the planning, coordination, and execution of their fraudulent acts. And so on up the chain.

As far as it goes.

And it seems to go far. Historian Heather Cox Richardson, writing in her January 17 newsletter, lays it all out in detail, leading to the inescapable conclusion that the scheme “appears to have been a coordinated attempt by members of the Trump administration and sympathizers around the country to overturn our government by committing election fraud.”

When the last person compelled to testify has had his or her time in the barrel before a grand jury, what started as a politically impeccable investigation of a mundane crime committed by nondescript individuals—like the investigation of the five Watergate burglars—could bring down the whole edifice.

Is it too much to hope for that the simple act of investigating a mundane fraudulent act could lead to widespread accountability in Trump World? Let’s find out. All it will take is for the Department of Justice to begin an investigation—for Attorney General Garland to prosecute the obvious crime right in front of him—and then to follow the facts upward as far as they go.